Ever heard of a private security contractor name Paravant? XPG? No? Well, that’s just as Blackwater, the parent company of Paravant, XPG and dozens of other “subsidiaries”, would have it. As a former Paravant Vice President noted in Senate hearings earlier this year, Paravant and Blackwater were “one and the same,” with Paravant created in 2008 to put aside Blackwater’s “baggage”. But then again, we probably shouldn’t be calling Blackwater Blackwater, since the company itself changed its name to Xe in 2007, hoping to get a fresh start in the race for wartime contracts from the U.S. government.

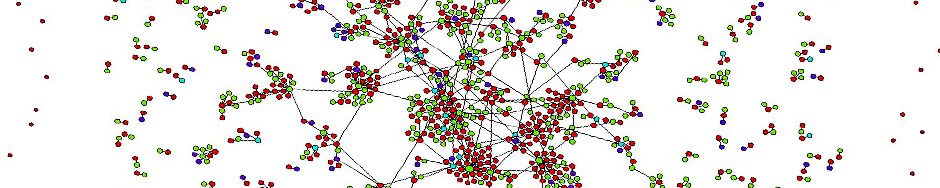

The New York Times reported last week the story of Blackwater and its “web of more than 30 shell companies,” and this is not just a case of corporate rebranding on steroids. Blackwater’s machinations and continued battlefield presence have been made possible by systemic changes such as a sharp decline in government’s ability to oversee the work and even functions that have been increasingly outsourced to private companies. These changes are part of a new system of power and influence that made its debut after the Cold War’s end. At the pinnacle of this system is the “shadow elite”. That’s the title of Janine’s book in which she identifies a new breed of power broker who bend the rules and play with their identities to best press their own agenda. They shuttle back and forth among roles of power in official and private organizations, gaining and hoarding vital information at each stop to serve their own, not their organizations’, interests. And they take advantage of the ambiguity at the murky spaces where state and private power meet, because with ambiguity comes a crucial asset: deniability.

Blackwater creates deniability in (at least) five ways. First, there’s the obfuscation created by the shell companies themselves. Once the name “Blackwater” became radioactive, the company, like the most nimble players of the shadow elite era, recrafted its image and corporate structure, if not its practices, to achieve the same old agenda. Blackwater could continue to peddle its services through those subsidiaries.

Second there’s the ambiguity of purpose of government officials — and the deniability that it lends them. As the Times puts it:

Army officials said [during a Senate hearing earlier this year] that when they awarded the contract to [shell company] Paravant for training of the Afghan Army, they had no idea that the business was part of Blackwater.

There’s no apparent reason to doubt those Army officials, but is that true for all of the contracts secured by Blackwater’s renamed units? It’s not hard to imagine the benefits of deniability to government officials who might want to use Blackwater’s services, but are wary of the public relations toxicity. They can say they just didn’t know they were dealing with Blackwater.

Third, there’s the deniability implicit in hiring foreign contractors to perform sensitive and dangerous U.S. work. An internal email obtained by the Times shows just how much Blackwater tries to market this kind of deniability. A Blackwater executive actually uses the word in describing why the government, in this case the Drug Enforcement Administration, might be interested in the services of a private spy network set up by Blackwater. Blackwater official Enrique Prado is quoted as writing, “these are all foreign nationals…so deniability is built in and should be a big plus.” (It’s worth noting that Prado, in true shadow elite fashion, brought government experience to his work at Blackwater — he’s “a former top CIA official,” according to the Times.)

Fourth, Blackwater benefits from the deniability that comes when the mechanisms of government oversight have broken down, and chains of command are hard to discern, the systemic nature of which Janine explains in a new report, Selling Out Uncle Sam: How the Myth of Small Government Undermines National Security. Take the case of the deadly incident that was the focus of those Senate hearings — by the Armed Services Committee — mentioned above. The Times refers to the 2009 incident, in which two Paravant workers fired their weapons and killed two Afghan civilians, and a read of the Senate hearings shows how tangled the lines of authority apparently were. From the Committee Chairman, Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.):

Army contracting personnel .… said that one way they monitored the contractor’s performance was from their office in Florida, and that was by checking in with Colonel Wakefield … in Kabul. However, Colonel Wakefield .… told the committee that Task Force (TF) Phoenix, a subordinate command, had oversight responsibility. Even after the May 2009 incident, a review of policies at Camp Alamo uncovered continuing ‘uncertainty’ as to what ‘authorities and responsibilities are over contractors,’ including ‘disciplinary issues’.

Who do you blame when no one can pin down who was really responsible in the first place?

Add to the confusion the fifth opportunity for deniability: in the case of the Paravant deal (and countless others throughout the contracting universe), this contract was actually a subcontract — with another defense firm, Raytheon. As seen in the Senate hearings, teasing out what Raytheon’s oversight role exactly was is no simple task. Again, ambiguity makes accountability a near impossibility.

Ambiguity is not an accident. As Janine writes in Shadow Elite, ambiguity is a key feature of the new system of power and influence, and it serves power brokers an important function. They can play different sets of constraints off each other, skirting accountability in one venue by claiming they were operating in another. They need not necessarily break the rules; they merely shift around them. Ambiguity is what affords actors deniability: while advancing their own agendas, they agilely defy scrutiny and public accountability.

The Times quotes Rep. Jan Schakowsky, an Illinois Democrat, who doesn’t understand why the government keeps giving Blackwater work:

I am continually and increasingly mystified by this relationship.….to engage with a company that is such a chronic, repeat offender, it’s reckless.

Reckless, yes, but to our eyes, not surprising.

One of the more infuriating aspects of the shadow elite is the ability to seize new opportunities, fresh deals, no matter how egregious the track record. The overarching reason is that those on the other side of the deal are getting something too. In Blackwater’s case, the government wants some of the dangerous and dirty work of war carried out by hired guns, not uniformed U.S. forces. And they apparently want to maintain the ability to point the finger elsewhere when, as was the case that night of May 5, 2009 on Jalalabad Road in Kabul, things go horribly wrong.

By Janine Wedel and Linda Keenan

Published in The Huffington Post, September 9, 2010.